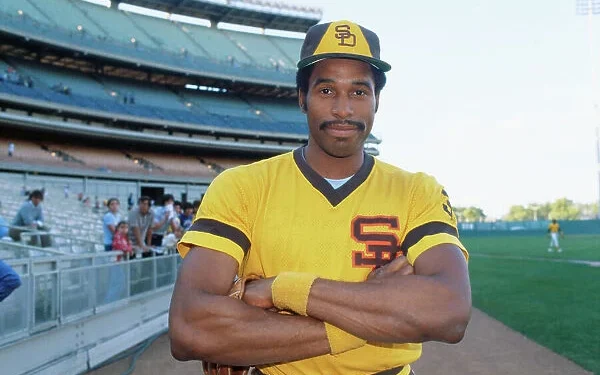

After a Major League Baseball game in the 1970s, emerging talent Dave Winfield had a conversation with a young boy’s parents that made him aware of his influence beyond the baseball field. “I will always remember what the father shared with me that evening. He remarked, ‘My son aspires to grow up and emulate you.’

“As a young player, those words truly resonated with me and prompted reflection on who I aspired to become. I dedicated myself,” Winfield, now 59, states. “I was willing to invest my time, resources, and anything else I could to help create a positive impact.”

During his remarkable 23-year tenure with five major league teams, Dave Winfield accumulated 3,110 hits and 450 home runs, earned seven Gold Glove Awards, was selected as an All-Star twelve times, and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2001 on his first eligibility. However, what many may not know about Winfield are his illustrious “hall-of-fame” achievements off the field. He is the pioneer professional athlete who established his own charitable foundation, paving the way for future generations of athletes.

Starting in 1973, his inaugural season with the San Diego Padres, Winfield began contributing by building friendships with local children living in the vicinity of the stadium. “Many of these kids couldn’t afford tickets, so I took the initiative to buy tickets, treated them to hot dogs and souvenirs, and provided them with an authentic ballpark experience,” he explains.

He escalated his efforts by purchasing additional tickets for children, and media coverage of his initiatives inspired volunteers and support from local businesses. To manage fundraising and operational costs, Winfield’s agent assisted him in establishing the Winfield Pavilion program, which became the first 501(c)(3) charity formed by a professional athlete.

Surprisingly, not everyone embraced his endeavors. “When I initiated my charity, many individuals and media questioned my intentions,” he recounts. “A lot of them assumed it was merely a tax strategy, not understanding my perspective—my thoughts, feelings, and upbringing.”

Hailing from St. Paul, Minnesota, Winfield experienced a modest upbringing, stating, “My mother firmly impressed upon my brother and me the priority of education in our household.” His extended family also played a crucial role in providing support and encouragement. “Our family looked out for one another.”

Blessed with an exceptional combination of physical attributes—size, agility, and strength—Winfield attended the University of Minnesota, where he excelled in both baseball and basketball. In 1973, he was named MVP of the College World Series as a pitcher and became the first individual to be selected in three sports: baseball by the Padres, basketball by the Atlanta Hawks, and (without ever having played) by the Minnesota Vikings in the NFL. Opting for baseball, he notably became one of the few players to totally skip the minor leagues.

Disregarding the skeptics, he persevered with his charitable mission. “With most games taking place at night, I dedicated my days to recruiting individuals for the board of directors and learning the intricacies of running a foundation.”

He emerged as a mentor for fellow players and children alike through the Winfield Pavilion. Soon, other athletes began to replicate the program in cities like Los Angeles, Atlanta, Chicago, New York, and Houston. Beyond its mission of assisting underprivileged children, the Pavilion program engaged thousands of youth with the sport. Notably, one of its beneficiaries was David Wells, a teammate from the Toronto Blue Jays, who grew up in San Diego and had attended one of the Pavilions as a child. As Winfield remarked, “You know you’ve been playing for a while when your peers tell you they looked up to you during their childhood.”

However, Winfield aspired to expand the foundation’s mission beyond merely attending baseball games. “We had these kids for the whole afternoon, and we wanted to provide them with more than just a game experience.” He recognized the fundamental aspects of his own success—health, wellness, and education—and incorporated these as primary objectives of his foundation.

In 1977, he collaborated with the Scripps Clinic and Research Foundation to develop H.O.P.E (Health Optimization Planning and Education), a comprehensive initiative promoting proper nutrition, regular exercise, medical and dental examinations, literacy, and behaviors conducive to good health.

“Back in the late 1970s, conversations about healthy eating habits for children were virtually nonexistent,” Winfield recalls. “If healthy lifestyle choices and study habits are instilled at a young age, there’s a strong possibility they will persist for a lifetime.”

The foundation coordinated clinics in the parking lot of the stadium, where children received non-invasive medical and dental assessments, vitamins, toothbrushes, and informative materials regarding diet and wellness. Other major league cities began hosting similar clinics, and Winfield reports that over 40,000 children have reaped the benefits. One outcome of these clinics is the Dave Winfield Nutrition Center at Hackensack (N.J.) Medical Center, which continues to provide nutritional counseling and evaluations.

Starting in 1976, the foundation also began offering scholarships to deserving students to bolster the educational component of its mission. This initiative originated in St. Paul before expanding to New York City, where, from 1981 to 1986, it awarded $40,000 annually to over 100 public high school students each year.

In 1984, the Winfield Foundation broadened its reach once more by introducing a substance abuse prevention initiative. “Traveling for baseball allowed me numerous opportunities to connect with youth from diverse backgrounds about their unique challenges and concerns,” Winfield states. “The primary ongoing risk for youth, both then and now, is substance abuse.” To develop the program, he consulted with officials from the federal Drug Enforcement Administration, who revealed research showing that kids began using drugs as early as age 10, he notes.

“The key is early intervention and prevention. Yet, there were no programs addressing children in grades 3 to 6. We named our initiative Turn It Around. It emerged as both a profound message to children and a call to the community to get involved.”

Turn It Around utilizes an interactive video and activity guide to educate participants about the factors contributing to substance abuse, as well as five areas deemed essential in prevention: developing self-esteem, making choices, identifying goals, fostering trust in others, and creating positive alternatives. The program includes a comprehensive training session for adult leaders and has been launched nationwide, even reaching areas outside the United States.

After concluding his playing career with the Cleveland Indians in 1995, Winfield decided to focus on family. “My children were young when I retired, and it was time to dedicate more attention to them,” he shares, having been married to his wife, Tonya, since 1988.

However, it wasn’t long before Major League Baseball sought his expertise again. In 1996, the Major League Baseball Players Association appointed Winfield as an advisor during the establishment of the Players Trust, another 501(c)(3) charitable organization. Through the Players Trust, professional players can contribute portions of their salaries to causes they care about, providing assistance to countless individuals in need across the globe. “I aided in navigating them through the formation process and offered insights on what was effective and what wasn’t based on my experiences with my foundation,” Winfield explains.

“Reflecting on my journey, I am immensely thankful for those who helped shape me into who I am today,” Winfield expresses. “They instilled within me a commitment to assist others. The true reward from my foundation has never been financial; rather, it lies in my ability to create, educate, inspire, and engage. Witnessing the profound impact we have made on so many lives has been genuinely awe-inspiring.

“Knowing that we’ve positively changed lives is the ultimate reward.”

In 1978, Dave Winfield’s charitable work faced a significant hurdle when he intended to bring 500 children to the All-Star Game in San Diego. During a television interview, Winfield mistakenly invited “all the kids of San Diego.”

This resulted in an overwhelming turnout of around 10,000 children, prompting him to convince the Padres to open the park early so the kids could watch batting practice. Additional sponsors stepped up to provide more food and souvenirs for the unexpected crowd.

Major League Baseball subsequently adopted Winfield’s solution as a tradition for the All-Star Game. Following his example, the league now opens all All-Star Game batting practices to the public, utilizing the opportunity to raise funds for local charities.